Archive

Relaxing Sunday Lunch at Lee & Tony’s Place (Blessington)

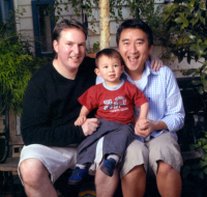

Today the weather was perfect and the company equally so! Jeff, Ethan and I ventured to Lee and Tony’s home in St Kilda for a relaxing Sunday afternoon lunch and for some a swim. Doug & Brett together with the twins (Leah and Daniel), Jason and Ruben (unfortunately Adrian had to work), Lee & Tony together with Xan and Luci. We had a great time and the kids got on great. The highlight for me was seeing Luci and Leah on the bed together chatting and playing together like teenage girls! Cute and a wonderful sight. Ethan didn’t eat (as usual) but we all had a great time. Lee and Tony are always such generous hosts!

Melbourne Leader – "Life’s Indian Givers" by Hamish Heard

Gay Dads Australia spokesman Rodney Cruise said gay Melburnians could save about $90,000 by using Indian surrogate mothers.

It is illegal for gay couples to have babies via surrogacy in Australia. But during the past seven years many have flown to the US or Canada where they pay about $120,000.

“Gay couples who previously wouldn’t have been able to have children because California is too expensive can take up the Indian option for basically a quarter of the cost,” Mr Cruise said.

“We’re seeing more and more couples take up the Indian option,” he said.

Mr Cruise said surrogacy cost only $30,000 in India.

Most of the money is paid to the surrogate, a woman who agrees to carry an embryo in her womb for the term of the pregnancy before giving birth and handing over the baby. Mr Cruise said couples could conceive using anonymous donor eggs or eggs donated by a relative or friend.

“Mostly it’s gestational, where the surrogate carries an embryo that has been created outside the womb. The surrogate rarely would use their own egg,” Mr Cruise said.

Until couples cottoned on to Indian surrogacy, only older, better-off couples could afford children.

“Generally people have been mortgaging their homes to fund this, and that’s fine for people who are in that position, but it can be heartbreaking for those without the resources to do so,” Mr Cruise said.

He said the “vast majority” of Australians using overseas surrogates were from Melbourne.

“There’s probably 40 couples that I know that have had children via surrogacy.” He said many gay couples had been inspired by a 2003 documentary called Man Made: Two Men and a Baby, about Tony Wood and Lee Matthews, a Melbourne couple who became one of the first Australia to produce a baby using an overseas surrogate.

“Maybe Melbourne is just a town where people settle down, or it could be the fact that the pioneering couples were from Melbourne and that’s had an effect of inspiring others around them,” Mr Cruise said.

[Link: Original Article ]

The Age – "The Surrogacy Journey Must be Respected" by Jenny Sinclair

Victoria’s legislation promises ethical and medical support.

WHEN the Victorian Government finally tabled its legislation for assisted reproductive technology last week, legal surrogate pregnancy came one step closer, along with access to IVF for gays, lesbians and single people.

Both major parties have said they will allow a conscience vote on the legislation, which is based on an extensive Law Reform Commission process.

While the MPs examine their consciences, they might like to consider what’s gone on in mine, and those of people like me, over the past four years. That’s how long I’ve been waiting for those documents to hit the table in Spring Street. Four years ago this November, I was diagnosed with breast cancer. The news came on the first birthday of my son, himself an IVF baby. Our plans for a second child were thrown into disarray as I plunged into

surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and long-term hormonal treatment. But unlike many women with cancer, I was lucky enough to already have eight embryos in storage from my IVF treatment. The door remained open.

Those embryos, stored in a supercooled vat in East Melbourne, have been hostages to the political process ever since. (The commission began looking at the issue way back in June 2002.)

My treatment — and the continuing doubt over the role of hormones in triggering a recurrence — put a five-year and possibly permanent bar on my carrying a baby myself. As the mother of a small child, I don’t have the right to increase the risk to my life; I have a duty to survive. But I was getting older — I’m now 42 — and the gap between my son and any siblings was growing daily.

Surrogacy seemed like the obvious solution, but as the Law Reform Commission observed, Victoria’s laws were inconsistent to say the least. A surrogate would have to be infertile herself, with an infertile partner, and technically, moving the embryos interstate or overseas for treatment would be illegal if the purpose of the move was surrogacy.

If the legislation now before the State Parliament passes, I will be able, if I can find the right person, to “commission” a surrogate pregnancy — to bring one of those frozen embryos into the light legally.

But even when the new laws take effect, I’m not sure that I’ll do it. Because I have, in reality, had the option of surrogacy all along.

For those four years, I’ve been noticing something: even with the laws as they are, people do it. A gay male Victorian couple who took a filmmaker to the US to document their “journey” did it (and have gone back for a second child). A senior federal Labor senator and his wife went from Victoria to NSW to do it, although their particular circumstances differed from mine.

People do it all the time: people with money, that is. Paid surrogacy is a reality in not only the United States, but in shadier operations in Eastern Europe and the Third World. And on the altruistic side, some women are carrying “traditional” surrogacies via self-insemination, often under the radar of the authorities. When it doesn’t require government resources and hospitals, you can get away with that.

My IVF experience, not to mention experiencing cancer, has taught me one thing: it’s futile to compare one person’s pain and needs with another’s. But when I think about using a surrogate — the usual term is “commission” but I can’t shy away from the knowledge that we’d be using another person to produce our child — I also think about the risks.

In Australia, surrogates are generally women who already have children, and I am all too aware of the horror of a child losing its mother. Under the proposed Victorian law, surrogates cannot be paid (apart from defined expenses), and while I would only want to work with someone who had altruistic reasons for helping me, I would, frankly, prefer to be able to pay some amount, if only to allow her to take enough time off work, to hire a cleaner, have help with her own kids, and to use private medical facilities.

Pregnancy is hard work. This is not Baby Mama: this is real life.

What the proposed Victorian legislation does is to recognise that surrogacy is something that is already happening, and to bring it into our excellent assisted reproductive technology system, with its ethics committees, dedicated counsellors and stringent medical standards.

But the decision to be, or commission, a surrogate, will still be made one person at a time.

The proposed laws will open up access to assisted reproductive technology, not just to married heterosexuals like us, but to gays, lesbians and single people. I welcome this because I believe they have the right to that access, and I welcome it all the more because their battle has become my battle too.

At some level, too, I am pleased that this Government, after years of this issue being on the backburner, has had the political will to reject the campaigners who tried to dog-whistle homophobia by focusing on the “gay IVF” angle and pushing my family’s situation, and those of other heterosexual families, aside.

Conscience, as the MPs well know, is an individual thing. Allowing people to act according to their consciences is to treat them as adults, and adults who can be trusted to make the right decision. The lower house of the Victorian Parliament has already paid Victorian women and their partners this compliment in regard to abortion law reform. When it comes to deciding on surrogacy, I look forward to the honourable members extending the same respect to me, my husband and to others in our situation.

Jenny Sinclair is a Melbourne writer.

[Link: Original Article]

SBS TV – "Two Men & Two Babies" by Emma Cummings

“It is five years since Alexander’s birth, and Tony and Lee now have a second child, Lucinda through surrogacy. Same egg donor, same surrogate. The sequel documents the intervening years since Alexander’s birth and provides a unique insight into the world of this alternative family”.

Two Men & Two Babies – “A follow-up documentary that takes audiences back into the lives of Tony Wood and Lee Matthews, one of the first Australian gay male couples to take what was then, the controversial step of creating a new family through commercial surrogacy in the United States”

Man Made: The Story Of Two Men & A Baby “explored Tony and Lee’s overwhelming desire to have a child, their decision to pursue commercial surrogacy, and their fraught journey to Cedar Rapids, Iowa to experience the birth of their son Alexander to a surrogate, Junoa”.

The Age Green Guide – "Dads Double Their Brood" by Larry Schwartz

Dads double their brood – Larry Schwartz revisits two men and their second child and film.

TWO Melbourne men, featured in a 2003 documentary showing how they turned to a Los Angeles agency to have a baby because commercial surrogacy is illegal here, were looking forward to a second child.

Tony Wood and partner Lee Matthews faced a new challenge. “When we found out that our second child was a girl, we were delighted,” says Wood, an employment lawyer at a large city firm. “But in a sense a boy would have been easier because we understand boys and we know how men work.

“I’ll tell you, having a girl’s the most enlightening experience. As much as you might want to say, ‘I’m not going to gender-stereotype this child’, she bloody well loves pink dresses and dolls and all that kind of stuff. It’s amazing. It’s a wonderful experience. We love her to pieces.”

Lucinda, whose arrival is featured in the follow-up documentary, Two Men and Two Babies (part of SBS’ Future Families series) is two years and three months old. She was born to Junoa, who also gave birth to her five-year-old brother, Alexander.

When I interviewed the couple almost five years ago before the screening of the first documentary, Man Made: The Story of Two Men and a Baby, Matthews, a businessman now in his late 30s, said he hoped Alexander would grow up to be straight so that he would have “one less hurdle to jump”.

“We just want them to be fulfilled in their own desires and their own expectations,” says Wood, reminded of this comment. “And they will be what they will be.”

They are among the first gay men in Australia to have children this way. Wood says they now know of about 20 children born through commercial surrogacy.

But two men and a pram is still a relatively unfamiliar sight and some people ask questions. “They say, ‘Where’s mum?”‘ says Wood. “And you say, ‘There is no mum. There are two dads.”‘

While laws in most Australian states and territories are restrictive, the ACT permits altruistic (non-commercial) surrogacy. Wood says he and Matthews would have preferred to adopt but this is not permitted here.

In the new documentary, he says commercial surrogacy “can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars” and he regrets that it can be prohibitive.

He says he and Matthews agreed to the second documentary despite “a high degree of ambivalence”, partly because director Emma Crimmings, who received an Inside Film Award and Logie nomination for the first Man Made, is a friend.

They reasoned also that the early documentary had helped inform gay men and educate others. “I think ultimately our intention is to break down discrimination and prejudice,” Wood says.

In the new film, Wood’s mother talks of her early misgivings about his homosexuality and the way he and Matthews planned to have a child. Thanks largely to encouragement from her friends after the first film, he says, she is now a doting grandmother. “In a sense she’s received the same kind of positive feedback that we have had. That’s wonderful to her.”

They are determined to be as open as possible with both children. “Alexander knows that his circumstances are not usual. Yet he also knows lots of other kids with two mums or two dads.”

They say they will not have another child and there will not be a third film. “It was filmed on and off over a period of more than six months,” Wood says of the second, “and, as much as you are friends of the filmmaker, you end up becoming at times less than best friends and very protective of your own personal time and space.”

He notes there are fewer unguarded moments in the second film and suspects you “become a less-interesting subject for a documentary the more familiar you become with the process.”

Was there anything he would have preferred not to see in the new film? “I would have made a very different documentary if I was editing it and there are certainly aspects that I would prefer weren’t included and there were obviously aspects I wish were better reflected in the film,” Wood says.

Filmmaker Crimmings met the couple socially through her partner, who worked with Wood. She says Wood and Matthews had “some contractual control. Ultimately they didn’t have final veto,” she says.

“But there was control in that when we got to the point where they would view the final outcome.

“If there were things there they took umbrage to and thought were not balanced and fair, then they would be reviewed and removed whatever the compromise was.”

[Link: Original Article]

Joy 94.9 Breakfast Show – Anthony Wood talks about "Two Men & Two Babies" to Andy and Adrian

Tony Matthews talks to Joy 94.9 Gay and Lesbian Radio’s Breakfast show about the upcoming documentary “Two Men & Two Babies”. To listen to the audio, click here.

ABC Radio – "Live Interview with Lee Matthews & Tony Wood and Josh Fergeus" with John Faine

Six years ago, prevented from adopting a child, or accessing IVF facilities or commercial surrogacy in Australia, Tony Wood and Lee Matthews embarked on an international surrogacy arrangement that would take them to Iowa, America, for the birth of their son. This resulted in the film, Man Made: Two Men and Baby. Five years on, Lee and Tony have a second child, Lucy who is 2 years old. A second film Two Men and Two Babies airs on 29th January on SBS TV.

Josh Fergeus is 22 years old today. He was accredited as a foster carer 3 ½ years ago. His mother has been a carer since 2001, and together with his mother and brother they fostered 21 different children. Josh works for Anglicare Victoria in Training & Recruitment for Home-Based Care. This involves publicising foster care and recruiting, assessing, training and supporting carers and volunteers. He has been involved in Victorian Government’s new systems for training and assessing carers, training staff and carers in it’s use since early 2007. He is a member of the Victorian Government’s Home Education Advisory Committee and holds two Bachelor’s Degrees in Arts and Teaching (Secondary), and I am currently studying my Masters in Social Work.

To here the entire interview, click here.

MCV – "And Baby Makes Four" by David Knox

David Knox meets the faces behind the forthcoming TV program, Two Men and Two Babies.

“We agreed we wouldn’t be doing any form of 7Up series,” insists Lee Matthews. “And here we are again.”

Five years ago, Matthews and his partner Tony Woods allowed cameras into their lives when they embarked on the rather rare experience of becoming gay dads.

Man Made: The Story of Two Men and a Baby followed their journey to Iowa, where their surrogate, Junoa, gave birth to their son Alexander in 2003.

At the time their story was shown on SBS, it attracted considerable media attention, both positive and negative, as an evolving definition of that oh-so-complex term, the modern Australian family. Matthews and Woods quickly became community ambassadors whether they liked it or not, immediately personifying options for gay men, politicians and conservative foes all at the same time.

As filmmaker Emma Crimmings explains, that first film raised other questions that SBS was keen to explore. Surrogacy is one part of the family’s journey, but how would it resonate as Alexander grew up? With cameras rolling, she took a second look.

“What I expected to find was more layers, more complexity that I wasn’t able to provide in the first [film] because it was such a rollicking narrative,” she tells MCV.

“It was a road movie with a baby. But the second one appealed to me because I could go out another circle, if you will, to the extended family and see the ripples of the choices that they made.”

But Crimmings’ questions were ones that the subjects weren’t sure were worth asking.

“We actually said to her, ‘Are you sure you want to do it, because we’re bloody boring anyway’” tells Woods.

“The life that we lead is no different to 95% of the general public, but of course it’s that very ordinariness that makes the political point that we’re not some extremist group. We’re just gay men with a family who have the same issues. But the very ordinariness is what makes the story,” he adds.

The two men’s son, Alexander, is now five years old, in his third year of pre-school, while daughter Lucy, two years old and also conceived with Junoa, is in crèche.

“To put ourselves out there as a news story when we’re just an everyday family doesn’t quite gel. There’s really nothing to say. We get up in the morning, we feed our kids breakfast, we get them to school, we go to work,” says Matthews.

Yet in 2008, this normality is still denied equity. Woods and Matthews have both been actively involved with the Rainbow Family Council, through which they have developed friendships with dozens of families, many of whom were directly inspired by their own story.

Rainbow Family Council spokesperson, Felicity Marlowe, acknowledges the need to personalise gay parenting.

“Telling our stories is an important step towards social and legal recognition. It’s about winning the hearts and minds of the broader community and getting them to understand that our families are just like any other family, and that that love makes a family,” she says.

It’s no coincidence that ‘Love Makes A Family’ is the name given to a four-year advocacy campaign focussed on the rights of same-sex parents and their children, which is finally winning political reform.

“The Victorian State Government in December approved most of the recommendations that the Victorian Law Reform Commission put in its report, that was tabled in June,” said Marlowe of the struggle for political recognition.

“But they didn’t approve anything to do with adoption, which for people in Lee and Tony’s situation is a key issue. Because they don’t have a birth mother in the primary relationship.”

Stopping short of recognising non-biological parent remains a sticking point for gay and lesbian parents.

“You can only say it’s because there’s this apprehension in the mind of the legislators that gay people are not fit parents, or the community doesn’t believe they are,” Woods theorises.

Still, five years on, there’s reason for hope.

“It feels like 2008 will be a year of change a way from the social conservatism of this current decade. I feel optimistic that the kids will grow up in a supportive, accepting environment,” he concludes.

Such a future has definitely been shaped by his and his partner’s willingness to publicly share their story.

“The guys are very brave doing it again,” Emma Crimmings says. “Once they hop on board, they’re on board, which I find incredibly admirable. It’s not easy to throw yourselves out there warts and all, dressing gowns and all.”

http://www.rainbowfamilies.org.au

Two Men and Two Babies airs 7:30pm Tuesday January 29 on SBS.

[Link: Original Article]

Sydney Star Observer – "Gay dads have their day" by Ian Gould

THEY MAY REMAIN IN THE MINORITY, BUT OPENLY GAY DADS WILL CELEBRATE DIVERSE PARENTING MODELS THIS FATHER’S DAY

For Gary Hampton, coming out 20 years ago meant announcing himself as part of a group stereotypically seen as childless hedonists. But the then 17-year-old was not about to abandon a long-held dream.

“I always knew that I could be a father and when I came out as gay I didn’t discount that option,” Hampton said.

Twenty years on, Hampton has witnessed his ambition come to life. On Sunday he and his partner Andrew will celebrate Father’s Day as dads to their three-year-old son Oliver.

The Sydney couple will join other men who, though part of a firm minority, are issuing a challenge to convention by parenting as openly gay men.

Determining how many gay men in Australia have children, and ascertaining the nature of their parenting arrangements, is a tricky business. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ most recent population and housing census, five percent of an identified 11,000 gay male couples in Australia had children, compared with about 20 percent of lesbian partners.

But the 2001 information made no distinction between offspring from previous heterosexual relationships and those from other parenting arrangements. Nor did it take into account single gay dads.

University of Sydney law academic Jenni Millbank, who has written major parenting reports for the NSW Gay and Lesbian Rights Lobby, said in her experience most gay men who were parents tended to have had their children with a former female partner.

In LGBT community consultations Millbank observed that when openly gay men formed families in partnership with another woman or couple, it was commonly “a friendly, avuncular relationship with the kids, ranging from casual to regular contact.”

Gary Hampton and his partner wanted more than that when they decided to become dads about five years ago.

After dismissing an international surrogacy arrangement as “unattractive and difficult-looking”, and with adoption in NSW out of reach for same-sex couples, the pair were introduced through a mutual friend to a lesbian couple who also hoped to become parents.

Hampton agreed to donate sperm, and after about six months one of the lesbian partners became pregnant.

Under a parenting model downloaded from the Internet – “a co-parenting arrangement for lesbian and gay parents … that spells out everything, areas of responsibility and that sort of thing” – the four parents-to-be agreed their child would live in each couple’s household half the time, after spending his first six months with his mothers.

It’s an arrangement that works well, according to Hampton, despite early insecurities and continuing scepticism from some. In contrast to his parents’ initial agreement, Oliver was about eight months old before he spent his first night with his dads, and almost two when he began living with his fathers 50 percent of the time.

“That was difficult for everyone involved because all of us were a bit insecure about our positions,” Hampton admitted. “I think there is a sort of culture among the gay male ‘donor dad’ people that shared parenting is too hard and doesn’t work. But for us it really does work.”

Oliver’s four parents have family planning meetings every two to three weeks, and communication between the mums and dads helps ward off possible parenting rivalry.

“Certainly we could go down that track of competitiveness … but they are general fears that everybody has,” Hampton said.

Not all gay dads are so keen on female involvement in the parenting process. Lee Matthews became a dad for the second time two weeks ago, and is quick to emphasise he and partner Tony are the only parents their two-year-old son and new daughter have.

“Our children have two dads who love them and look after them. They don’t have a woman as a parent. So because there is no female parent, there is no mother,” Matthews said.

The Melbourne man can make the assertion with confidence because he and his partner became fathers through a surrogacy arrangement in the United States.

The same surrogate bore the couple’s two-year-old son Alexander and new daughter Lucinda, both times using another woman’s egg and sperm donation by Matthews and Wood.

Commercial surrogacy arrangements like those taken up by Matthews and Wood are unlawful in Australia. Even where they are permitted – like in parts of the United States – a price tag running to the tens of thousands is often a deterrent.

But while commercial surrogacy’s critics resent what they see as a business-like transaction, Matthews’s experience has been positive. “We’ve received nothing but support from so many aspects of the broader community, including the crèche that our first child goes to, right down to good old playgroup or Mums’ group that the local council offers new parents.”

He attributes the outcome to an inner city postcode and a robust defence of their parenting model. “I think we have actually been quite proactive in asserting why we want to be parents and that may result in people not asking.”

“[And] I think with most aspects of being gay, as soon as you can personalise it, people look at you as individuals.”

Meanwhile, gay men hoping to independently form a family in Australia face a struggle. Fostering, adoption and surrogacy are the three main options, according to Jenni Millbank. But fostering is not usually intended as a permanent parenting arrangement. And since same-sex couples cannot adopt in NSW, gay men must apply as individuals.

“There is much less likelihood that as an individual you’re going to get an [adoption] order compared to a couple,” Millbank said. International adoption is also competitive and skewed towards heterosexual couples, while commercial surrogacy is unlawful in Australia. Altruistic surrogacy – where the surrogate receives no payment – is highly complicated and prohibited in many states if medical expenses are paid or advertising occurs.

Adding to the legal complexities is possible discrimination, an area in which gay dads’ experience appears mixed. Like Lee Matthews, Gary Hampton said he and his partner had yet to experience much serious prejudice. The pair appeared on Channel Seven’s Sunrise program this week in a bid to raise awareness of same-sex parents, but will decline media appearances once Oliver starts at school to protect their son’s privacy.

They will also ensure teachers and parents at Oliver’s school know he is from a same-sex parented family, and are hopeful their son won’t experience harassment.

But another gay father believes prejudice is a real issue for would-be gay dads to weigh up, particularly if women aren’t involved as parents. Paul van Reyk has fathered six children to different mothers since the 1980s through private sperm donation arrangements.

“I think that there is a significant part of the population who is entirely comfortable with two women having kids,” the Sydney 53-year-old said. “[But] I think that they’d be less comfortable with two gay men who chose to have a child where there wasn’t, say, a ‘mother’ somewhere involved.”

“There is still a really strong prejudice against the notion that [gay men and lesbians] are absolutely reasonable parents.”

Gay dads can also expect limited support options, according to another gay father Reymon Leglise. After the then married father-of-three came out as gay two years ago, he faced a battle.

“I spent six months either searching the web, going to forums, going to different groups and outings and anything else, trying to find some form of support for children [of gay and lesbian parents].”

Leglise eventually established social group Gay Dads And their Young (GDAY) late last year.

GDAY runs social outings for about ten gay fathers and their children, but Leglise said it and a similar organisation in Melbourne were rarities.

The prospect of limited support, combined with legal complexities and possible prejudice might be enough to warn many gay men off fatherhood. But Lee Matthews dismissed those fears in the lead-up to his first Fathers Day as a two-time dad.

“It certainly cools the lifestyle down, there’s no doubt about that,” he said of parenthood as an openly gay man.

“But it opens up whole new social experiences that are quite wonderful and rewarding.”

[Link: Original Article]

The Age – "Fathers and son" by Annmaree Bellman

A new film follows two Melbourne men’s quest to become gaydads . By Annmaree Bellman.

AFTER three years of IVF, a Melbourne couple are counting the days to the arrival of their first child: decorating the nursery, buying up big at Babyco. They’re ready for the dash to the hospital – in Iowa.

Tony Wood and Lee Matthews are gay. Prohibitive Australian legislation about same-sex parenting has led them into an expensive overseas surrogacy deal. They’re flying to America not just to meet their baby, but its birth mother. Filmed at claustrophobically close quarters, their pursuit of parenthood makes for one heck of a road movie.

The story’s complexities intrigued director Emma Crimmings when she learned of their plan three years ago. Tony worked at the same law firm as her partner and had even appeared in one of her earlier films, but he and Lee refused an initial request to document this experience. “It was too confronting,” says Crimmings, who studied documentary-making in the University of Melbourne’s VCA program. “It wasn’t until they got pregnant that we talked about it seriously, about what would be involved and whether they would be willing to take that leap.”

The leap was considerable. Crimmings was a friend but the film is no glowing tribute to surrogacy, nor a glib treatise on gay parenting. The couple’s desire to be parents collides constantly with the bald realities of buying a baby. Empathy with their predicament and connection with these humorous, committed, anxious dads-to-be takes flight, for instance, with the news that the Iowan mother-of-two having their baby might not breastfeed. Negotiations loom. “We have always wanted to be able to access our surrogate’s colostrum,” says Tony. It exemplifies the unflinching nature of a film that simultaneously delights and discomforts.

“When they first saw the film, there were lots of things in it that were deeply confronting,” says Crimmings. “There’s not a lot of people who could deal with having that mirror thrown at them, particularly in such an intimate context. We negotiated some things but overall they permitted me to make the film I wanted.” They participated not least because it highlighted the situation of gay couples wanting children in what Crimmings describes as “1950s Howard Australia”.

“They have an agenda – they’re political about this issue and the only way change is going to be invoked is through awareness and, as Tony said, it’s like the best-quality home video; a legacy for (their son) Alexander.”

Crimmings began shooting in July 2002, her job as curator of projects at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image shoehorning the film into weekends until it came time to board the plane last December. It is a starkly intimate film, Crimmings trapping faces in close-up, capturing quips, spats, frustration. The emotional tension accelerates when we meet Junoa, the surrogate mother whose outward serenity belies evident conflict. Her participation, which adds immeasurable power to the film, almost didn’t happen. “I had a chat to the guys and said `Look, I think it will benefit the story and provide all of the aspects of this journey if she speaks. And it would soften it, frankly.’ The guys were understandably protective of her but after the birth Junoa gave us all a bit of a gift and agreed to be part of the project. I think she was actually thankful for the ability to externalise it.”

Junoa’s inner turmoil is largely unspoken, voiced instead by a midwife whose perspective, alongside that of the head of the LA surrogacy agency who brokered the deal, is one of the film’s strengths. Their views, and the responses of other players along the way, answer the questions both the situation and audience demand. “This has got nothing to do with my politics or anyone else’s,’ says Crimmings. “It’s about revealing the story. As a viewer you search your own morals and ethics about what’s happening and you need all the information to do that. There is a commercial reality to this and an emotional reality (for Junoa). You don’t have to judge, but you have to ask questions.”

Condensing 50 hours of footage into 50 minutes became a feat of sensitivity. The result is a finely shaded portrayal with unexpected twists. Tony and Lee didn’t envisage Junoa playing a role in Alexander’s life after the birth but, as their relationship evolved, all three had to adapt to human rather than contractual imperatives. Junoa plans to visit the new family later this year. “There’s the complexity,” concludes Crimmings. “They entered into a commercial arrangement but it carries the comet tail of emotion. I think that even surprised the guys. They have a marvellous relationship with Junoa now, a real friendship, and she will play an important role, even if a distant one, in Alexander’s life.”

Two Men and a Baby screens on Tuesday at 7.30pm on SBS.

.bmp)